Scientists uncover protein with the power to help or hinder breast cancer progression

New research has shed light on how one of the most difficult-to-treat types of breast cancer defends itself against immune attack. The findings could help more patients to benefit from the latest advances in immunotherapies.

Dr Oliver Pearce and his team at Barts Cancer Institute (BCI), Queen Mary University of London, found that different forms of a molecule known as versican can either block or support the passage of cancer-killing immune cells into triple-negative breast cancer tumours.

Triple-negative breast cancer is one of the most challenging forms of breast cancer to treat. It grows rapidly and does not respond to the therapies most often used to target other types of breast cancer, such as hormone therapy. New clinical trials, including work led by the BCI, show that immunotherapies, which help our immune system to fight cancer, could provide a powerful option.

However, the success of these therapies has been limited by some cancers’ ability to shield themselves from immune attack. Tumours create a barrier around themselves, formed from a structure called the extracellular matrix, a scaffolding network that maintains the 3D shape and structure of our tissues. This barrier excludes immune cells such as T cells that could otherwise attack the tumour.

Dr Pearce and his team are investigating how components of the extracellular matrix block the immune system, with the ultimate aim of developing ways to break down this defence and render the tumour more susceptible to immunotherapies.

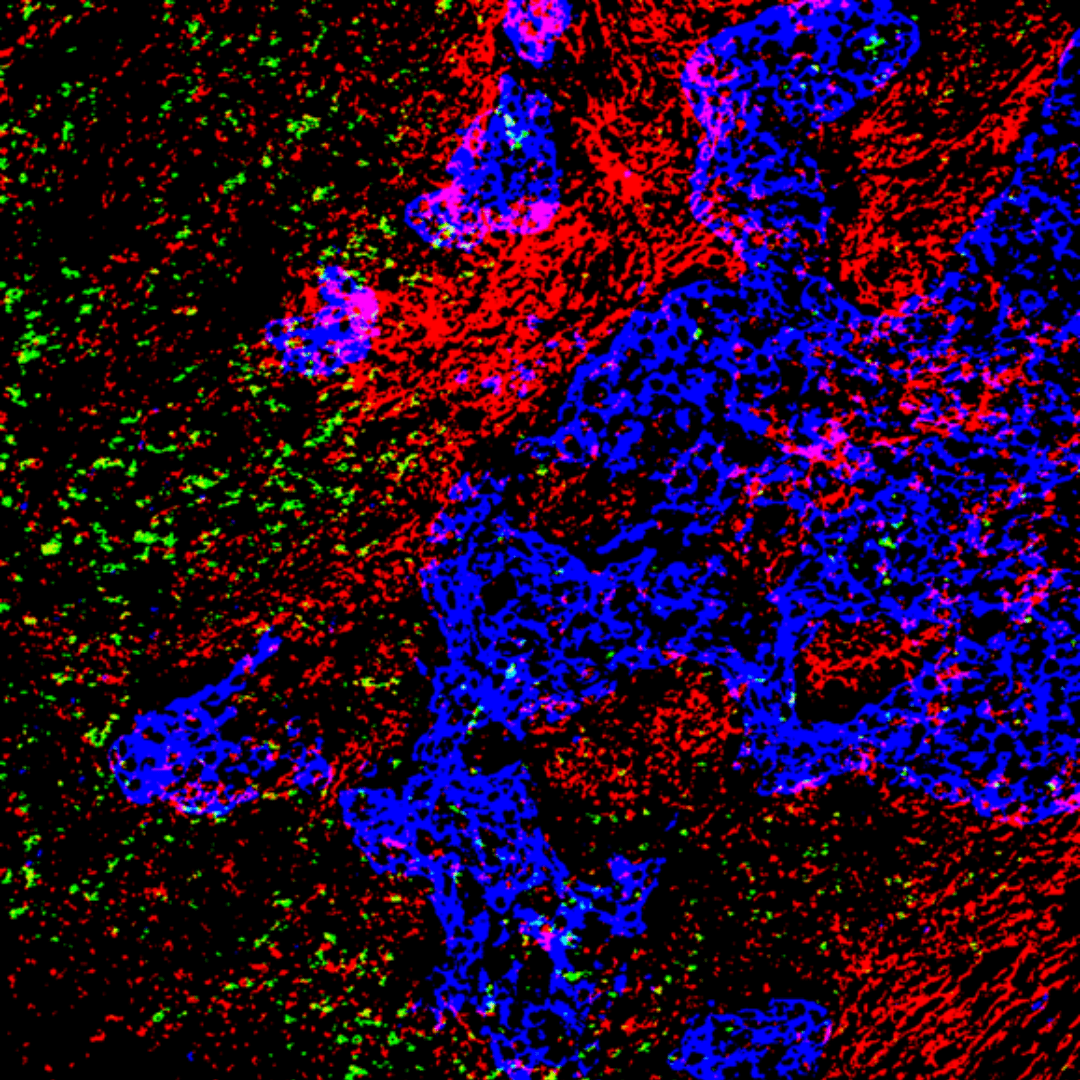

The lab’s newest study, published in Cancer Research Communications, was led by Dr Priyanka Hirani, who recently completed her PhD in Dr Pearce’s group. Dr Hirani examined tissues from patients with triple-negative breast cancer from the BCI’s Breast Cancer Now Tissue Bank and observed a link between a component of the extracellular matrix called versican and the location of T cells. She noticed that low numbers of T cells were present in areas with large amounts of versican.

To investigate further, Dr Hirani travelled to Seattle in the USA to collaborate with Dr Kimberly Alonge and her team at the University of Washington. Using cutting-edge mass spectrometry, the team found that the type of versican present was an important factor in how it affected T cells. Versican consists of a protein core that is covered in chains of carbohydrate molecules called glycosaminoglycans. The team discovered that depending on the pattern of carbohydrate chains, versican could either support or block the migration of T cells into the tumour.

“I think this is the most important finding. It’s not just about the amount of protein present – it’s about where the protein is located and how parts of that protein are creating the effect.” Dr Hirani comments. “One protein can have a completely different effect depending on how it is modified. Understanding these differences could eventually help us make more targeted therapies that have a better impact on patients.”

Dr Pearce comments: “The really surprising part of this work is that the different functions of versican to either support or inhibit T-cell movement came down to the location of a sulfate functional group, which would not have been detected using conventional mass spectrometry. This provides a striking reminder that tiny changes in molecular structure can result in very different, and in this case opposite, biological functions.”

“This provides a striking reminder that tiny changes in molecular structure can result in very different, and in this case opposite, biological functions.”

— Dr Oliver Pearce

The investigators suggest that by using an enzyme to degrade particular carbohydrate chains bound to versican, an environment can be created where T cells can more easily access the tumour, enabling immunotherapies to take effect. Further research is needed to test this hypothesis and determine whether versican also plays a similar role in other types of cancer.

This work was made possible thanks to funding from Barts Charity, Cancer Research UK and Against Breast Cancer.

Category: General News, Publications

No comments yet