Professor Sarah McClelland awarded £1.5m from CRUK to study cancer’s chromosomal chaos

Congratulations to Professor Sarah McClelland, who has received a £1,500,000 Programme Foundation Award from Cancer Research UK (CRUK), to support her lab’s work at Barts Cancer Institute (BCI), Queen Mary University of London. The funding will enable her to investigate the genetic chaos within cancer cells and identify new opportunities for therapies that target the source of this chaos. We spoke to Professor McClelland to learn more about this exciting area of research, her plans for this grant, and her advice for researchers seeking funding for ambitious projects.

What challenges are you tackling?

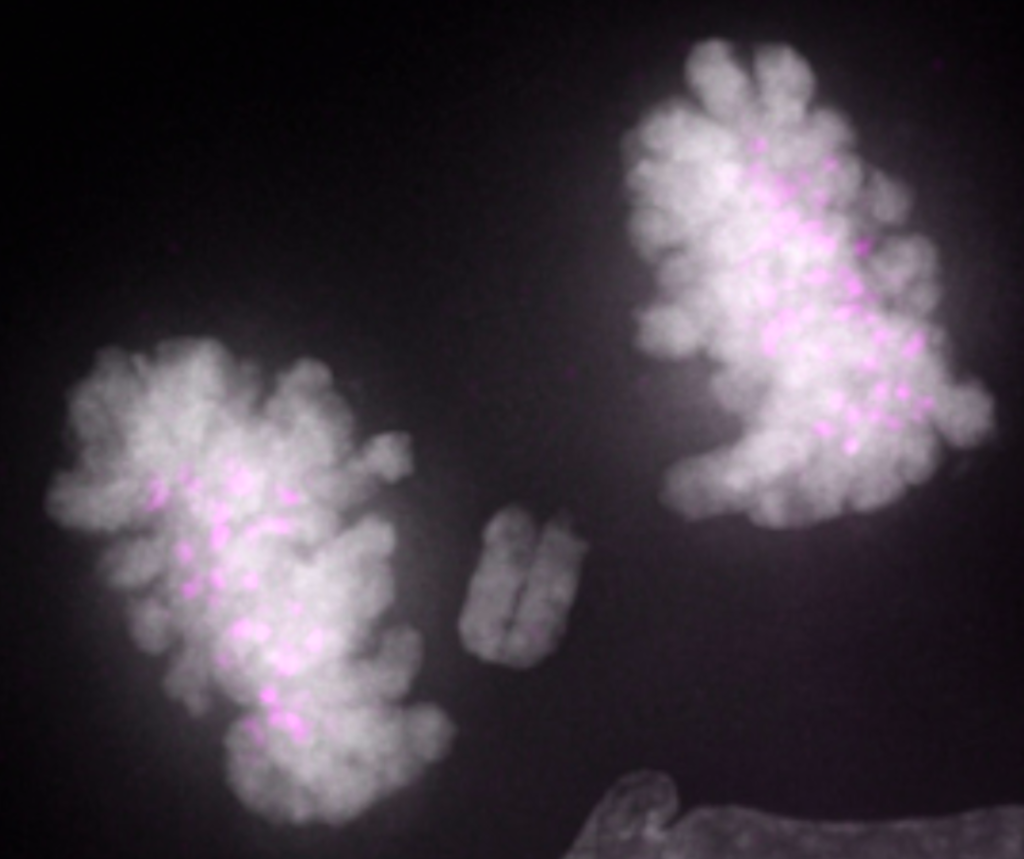

This grant will allow us to address a fundamental question in cancer research – why are cancer genomes so chaotic? Healthy human cells have two stable copies of each chromosome. By contrast, cancer cells often show drastic changes, such as variations in chromosome numbers, structural rearrangements, and duplications or deletions of DNA sequences.

However, we still understand very little about how and why this chaos emerges. It’s an incredibly complex puzzle. While we do see some patterns – for example, certain changes are more common in specific cancer types – we can't yet identify a logical cause for most of these alterations.

How could addressing these questions ultimately benefit people with cancer?

Understanding what drives these patterns – or whether they are random – is key. This knowledge could help us better diagnose cancer and develop more effective treatments. If we can identify the mechanisms causing certain alterations, we could potentially target them with therapies – similarly to how we currently treat cancers with faulty DNA replication by using drugs that worsen those defects, making the cancer cells self-destruct.

How will your research approach this problem?

Firstly, we want to create a ‘dictionary’ of different genome alteration patterns. We will grow cells in the lab, expose them to various stressors – such as drug treatments or targeted gene knockouts – and then observe how each change affects their chromosomes. This systematic approach will provide a much-needed reference guide linking specific patterns to underlying mechanisms, which will help us decipher the complex genomic changes seen in tumours.

Secondly, we will study cancer cells to understand how these patterns develop over time. Currently, when we analyse cancer genomes, we take an average of billions of cells, which means we only see stable, older alterations. But to develop effective therapies, we need to know what’s causing instability in a person’s tumour right now, not years ago. We'll grow cancer cells in the lab and track new genome alterations as they occur over a few weeks, using computational analysis. Then, we'll compare these changes with our dictionary of patterns to see if we can identify what's driving them.

How might these findings translate into the clinic?

Ideally, in the future, clinicians could take a tumour sample, look at the patterns in the cancer cells’ genomes, and determine whether the cancer cells rely heavily on a particular cell process, such as a DNA replication or repair mechanism. This might suggest that their patient will respond better to one treatment over another, enabling them to make more precise, personalised treatment decisions. Additionally, our findings could drive the development of new therapies that target previously unrecognised mechanisms of genomic instability.

Tell us more about your journey to securing this grant.

It has been a long journey, requiring a lot of determination and persistence! I first submitted a version of this proposal back in 2019, but it was initially rejected. After receiving some feedback, refining my ideas and reapplying, I was turned down a second time. It was disheartening, and I almost gave up on the idea.

After letting it sit for a few years, I had some valuable discussions with Professor Sir Steve Jackson from the CRUK Cambridge Institute and Professor Sam Aparicio in Vancouver, who are experts in DNA repair and single-cell sequencing, two key elements of the project. They encouraged me that the idea was worth pursuing and agreed to be collaborators on the grant, giving me the confidence to keep going and apply one more time. This time, I was successful!

"Research is rarely a straight path, but resilience and the right team can help you achieve your goals."

— Professor Sarah McClelland

What advice would you give to early-career researchers looking for funding for an ambitious research idea?

I would say: setbacks are a part of the process. If you still believe in an idea after a few years, it’s probably worth pursuing. Trust your instincts, gather feedback, and find collaborators who support your vision. Research is rarely a straight path, but resilience and the right team can help you achieve your goals.

Category: General News, Grants & Awards, Interviews

No comments yet