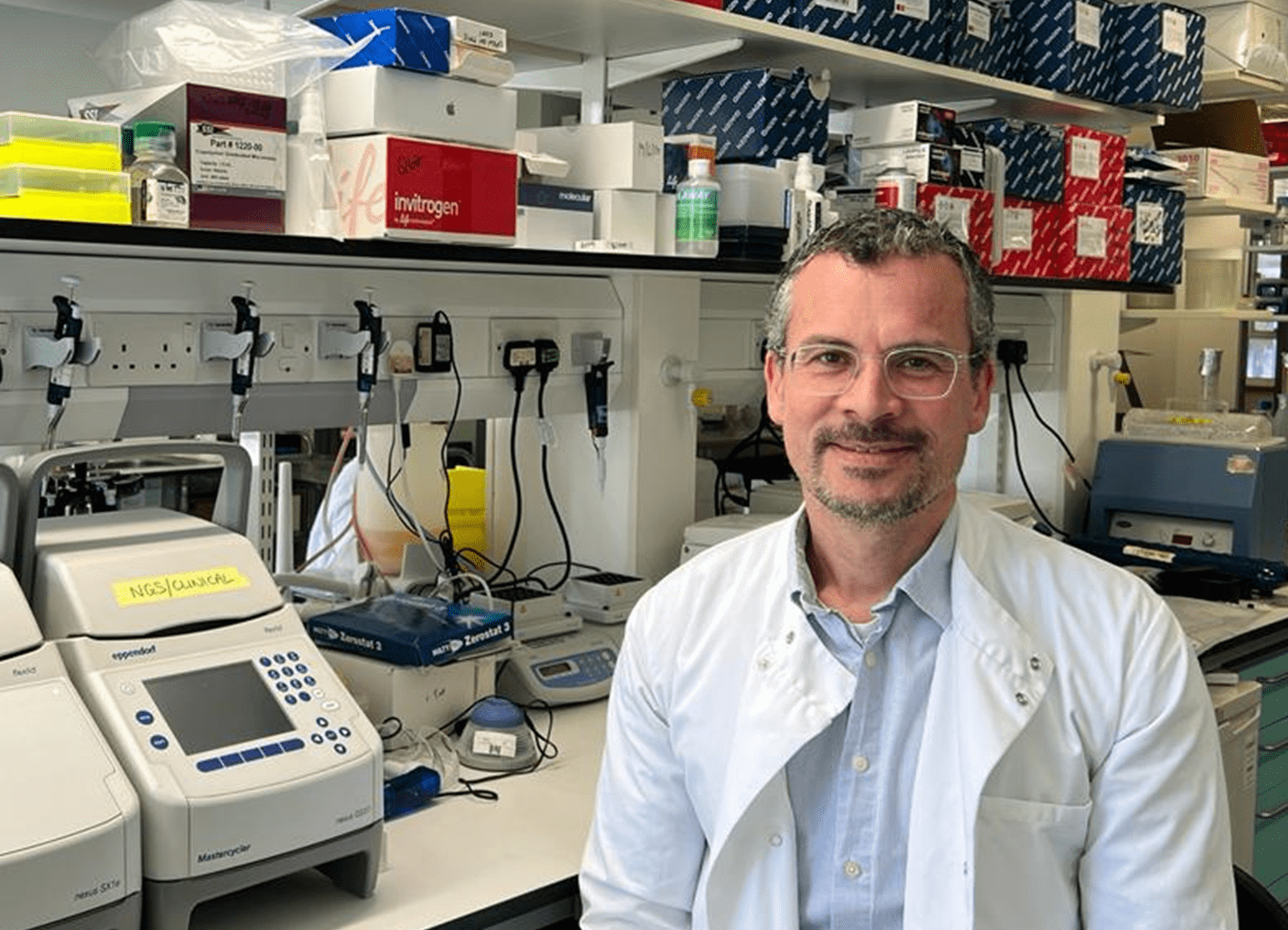

In conversation with Professor Marco Gerlinger

International Clinical Trials Day

Today (20th May) marks International Clinical Trials Day, which recognises the day that James Lind initiated what is considered as the first randomised clinical trial aboard a ship back in 1747, to find a treatment for scurvy. Almost three centuries later, clinical trials are a vital part of medical research, essential for finding new and improved ways to prevent and treat illnesses, including cancer.

This International Clinical Trials Day, we spoke with Marco Gerlinger, Professor of Gastrointestinal Cancer Medicine at Barts Cancer Institute (BCI), Queen Mary University of London, to find out more about his research.

Professor Gerlinger and his team joined BCI’s Centre for Tumour Biology earlier this year from The Institute of Cancer Research, London. The team’s laboratory research focuses on understanding and overcoming drug resistance in bowel and gastro-oesophageal cancers, and identifying new and more effective ways to treat these cancers using immunotherapies and combination therapies. The team’s research insights have informed several clinical trials investigating new therapies for these cancer types.

In addition to leading his research group, Professor Gerlinger is a Consultant Medical Oncologist at St. Bartholomew's Hospital where he treats patients with gastro-intestinal cancers.

Could you tell us about your research? How have your findings been translated into the clinic?

Our top priority is to do laboratory research that gives us clinically relevant insights. This should inform clinical trials that investigate new therapies for hard-to-treat bowel and gastro-oesophageal cancers. We are particularly interested in understanding the molecular basis of how these tumours develop resistance to cancer drugs, and find ways to overcome the resistance mechanisms by combining drugs in different and more effective ways. Our second focus is how we can improve the efficacy of immunotherapies, which work by harnessing the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

The main approach we use for identifying potential new therapies is to look at samples from patients who were treated with conventional cancer drugs or immunotherapies in clinical trials. By working with patient samples, for example tumour biopsies and even live cells that were grown from these, we can understand the molecular basis of cancers that have responded well to treatment and cancers that have responded sub-optimally. Once we identify the mechanisms that regulate therapy response, we try to work out if there is a molecular ‘switch’ that we can flick in order to make cancers more responsive to treatment.

We have successfully translated some of our laboratory findings into new clinical trials. For example, we have previously shown that treatment of bowel cancers using a drug called cetuximab, which blocks cancer cell growth, leads to an increase of immune cells called T cells in these tumours. With our collaborators at the Royal Marsden Hospital, we are now conducting a translational clinical trial to see whether patients who have received cetuximab can benefit from subsequent treatment with immunotherapy. Our hypothesis is that this will stimulate the T cells that were driven into the tumours by cetuximab to attack them.

What are treatment options like currently for people diagnosed with bowel and gastro-oesophageal cancers?

For metastatic bowel cancer, we are still heavily reliant on chemotherapy. Targeted drugs have been identified in the past two decades but most of them are only effective in small subgroups of patients or only give survival benefits of a few months.

Immunotherapies have changed the way several cancer types are treated but the large majority of bowel cancers have proven to be highly resistant. We want to find out why it is so difficult to trigger the immune system to fight these tumours, and how we can make immunotherapies work better. This is important because cancer cells we grew in the laboratory from multidrug-resistant bowel tumours could still be readily killed by T cells. This showed us that the immune system has potent effector mechanisms and that we need to find ways to bring T cells into these tumours and to activate them there.

In gastro-oesophageal cancers, immunotherapies are already changing the way we treat our patients. But they only increase the treatment response rate by approximately 10%. The question now is, with many new immunotherapies in development, which ones do we need to combine to push this response rate further?

Do you think your role as an oncology consultant affects how you conduct your research?

Yes, it influences my laboratory research substantially. In the clinic I can clearly see where our current limitations are – what patient populations do not benefit from existing treatments at all and where we need to be doing better in order to make patients with these aggressive tumours live longer. These clinical observations and results from clinical trials provide the main inspiration for the projects we develop in the laboratory.

By having this very close link with the clinic, I can make sure that we are addressing issues in gastrointestinal oncology.

What are your team’s research plans here at BCI?

We will expand our research into better immunotherapies for bowel and gastro-oesophageal cancers. We recently completed a number of immunotherapy trials at the Royal Marsden Hospital and our first priority here at BCI was to get the lab up and running and to start analysing these samples with cutting edge methods.

BCI’s links to the Barts Health NHS Trust with its large patient population also gives us a tremendous opportunity to expand our laboratory work on tumour samples from patients with bowel and gastro-oesophageal cancers and do more clinical trials.

A big gap in gastro-intestinal cancer research is that we have no effective way of doing preclinical testing of new immunotherapies in relevant model systems for these tumour types. We will establish a biobank of live cancer cells and live immune cells that will allow us to build model systems of these tumours in the laboratory and test how new immunotherapy combinations work. This is one of our key research aims over the next 2-3 years.

Category: General News, Interviews

No comments yet