Blood Cancer Awareness Month: how can we personalise treatments to improve care?

September is Blood Cancer Awareness Month. Here, Dr Lou Salomé Herman, a postdoctoral researcher in our Centre for Haemato-Oncology, reflects on the current challenges facing blood cancer patients and how we’re addressing them. In particular, she explains how her own work is exploring the ways blood cancer differs between men and women, and how we might better tailor treatments to each person.

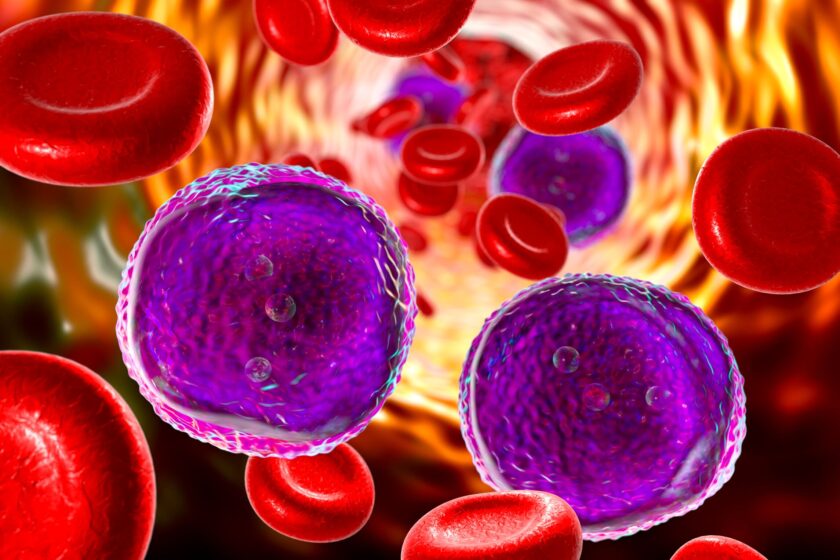

There are over 250,000 people living with blood cancer in the UK. Also known as liquid cancer, blood cancer affects different types of blood cells and can take many different forms. The most common ones are leukaemias (which affect white blood cells in the bone marrow), lymphomas (which affect white blood cells called lymphocytes) and myelomas (which affect white blood cells called plasma cells).

Collectively, blood cancer is the UK’s fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death. Most people who are diagnosed are not even made aware that their condition is a type of blood cancer. Despite being the UK's third deadliest and fifth most common cancer, blood cancer lacks public awareness, slowing research progress. More research is needed to understand these diseases better and develop treatments with better outcomes and fewer side effects.

One of the biggest challenges with blood cancer is that every single patient is different, with different genetics, different immune systems and different responses to treatments. This includes differences between men and women.

"One of the biggest challenges with blood cancer is that every single patient is different, with different genetics, different immune systems and different responses to treatments."

— Dr Lou Herman

Men are more likely to develop cancer than women, with 1 in every 16 men and 1 in every 22 women likely to develop blood cancer at some point in their lives. Men are more likely to experience a poor outcome, while women are more likely to experience side effects from treatments. Why blood cancer affects men and women differently is poorly understood, and it is something I want to address in my research at the Barts Cancer Institute. If we can understand where these differences exist, then we can assess their impact on current and future treatments, ultimately providing sex-tailored treatments and dosing with maximum efficacy and minimal toxicity for both men and women.

Tackling blood cancer in the Centre for Haemato-Oncology

Last year, I joined the Barts Cancer Institute as a postdoctoral researcher in the Centre of Haemato-Oncology. This centre houses 14 labs dedicated to better understanding leukaemias and lymphomas and is led by Professor John Gribben, whose lab I am a part of. We are in a unique position to implement our findings in the clinic due to our close relationship with the Haemato-Oncology department at St Batholomew’s Hospital Cancer Centre.

In Professor Gribben’s lab, we investigate how blood cancers affect our immune system and our innate ability to fight defective cells. In other words, how blood cancers evade our inbuilt safety mechanisms. We also investigate how to improve a type of immunotherapy called CAR-T therapy and drugs called Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitors. We are interested in understanding how these agents can make cancer cells more vulnerable to immune attacks while keeping the rest of the immune system intact.

Training patients’ own immune cells to fight cancer

CAR-T immunotherapy is a new cancer therapy that uses a patient’s own immune system to selectively target and kill cancer cells. A patient’s T cells are removed, modified and then put back into the patient to fight the cancer. The T cells are genetically modified to generate receptors on their surface called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), which allow the T cells to recognise and target cancer cells.

It is an incredibly potent immunotherapy for patients with aggressive and refractory blood cancer, improving survival. Although it has revolutionised treatment outcomes, specifically for relapsed patients, it comes at a great cost, in the form of adverse side effects.

There are very few studies addressing sex differences in CAR-T therapy, but the few that have looked into it have identified a link between the female sex and improved survival outcomes as well as lower relapse rates. Further research in CAR-T therapy is necessary and sex differences should be within the top priorities to reduce disease burden and sex disparity. As part of the Gribben lab group, one of my goals is to contribute to the field by including sex differences in my own work and encouraging colleagues to do the same.

Targeting the abnormal growth of immune cells

Cancer growth blockers are a type of treatment that disrupt the signals that drive cancer cell growth. BTK inhibitors are drugs that block the activity of a molecule called BTK, an important protein for the development and maturation of B cells. This slows the proliferation of malignant B cells, giving the host a chance to repair and strengthen the immune system.

My own research currently focuses on a type of blood cancer called Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL). CLL is slow-growing and develops over many years. People with CLL overproduce abnormal B cells that do not function as well as their normal cells, making them vulnerable to bacterial and viral infection. I’m looking at how different BTK inhibitors affect the host immune system after treatment in this type of cancer, as well as comparing the different treatments to one another.

Since men are more likely to get CLL than women, one of the things I am also investigating is whether or not the different treatments affect men and women differently. Sex is increasingly being recognized as a key factor in drug toxicity trials, yet it hasn't consistently been included in study designs. There’s a rising awareness of the importance of ensuring both sexes are represented in drug trials to develop more tailored and effective treatments.

My background is in infectious diseases and immunology, and my work has largely focused on the host immune response. I joined the Barts Cancer Institute to deepen my understanding of how our immune system functions while also gaining more insight into the clinical side and exploring a new perspective. I was not entirely surprised to find an absence of works looking at sex differences in CLL, though I was very disappointed by it.

"Lou’s novel approach to her work is already making inroads into understanding how males and females respond differently to treatment and this will surely open up new avenues to address how we increase the safety and efficacy of our treatments for blood cancer."

— Professor John Gribben

Learning from studies of sex differences in malaria

In one of my previous roles researching infectious diseases, my colleagues and I would routinely include sex as one of our analysis criteria, to determine whether or not there were any sex differences in the incidence, distribution, and control of malaria. Malaria is a parasitic disease transmitted by the bite of infected mosquitos. Many variables are usually included to determine whether there is a link with occupation, age, sex, location, type of housing and other factors. For instance, some of my work identified that men had higher risks of Plasmodium knowlesi exposure, one of the malaria-causing parasites in Southeast Asia that also infects macaques. This higher risk in men had to do with palm oil farming at the forest edge, an area more likely to be inhabited by infected mosquitos and macaques. If any links are identified it is then possible to ask why there is a link and how can we improve things.

Looking to the future

I hope my work will highlight the importance of including sex differences in cancer research.

Ideally, if we find significant differences between the sexes – for example, in drug trials – these should be considered by clinicians when making decisions about a patient’s treatment, where possible. Only half of oncology trials analyse data by sex, and the quality of that analysis is usually poor.

"Collecting more sex-specific data can greatly benefit blood cancer research by revealing inequities in treatment toxicity and effectiveness."

— Dr Lou Herman

One of the challenges is that women are usually underrepresented in clinical trials, with one of the reasons being that hormonal fluctuations could affect findings. Indeed, hormones in men and women have different effects on the immune system and these effects should be accounted for and studied.

Changing policies and treatment regimens according to sex could be challenging, as it would require additional clinical trials to implement any changes, such as drug dosages, if we detect toxicity and efficacy differences between sexes. Collecting more sex-specific data can greatly benefit blood cancer research by revealing inequities in treatment toxicity and effectiveness. This information can help shape future policies and guide clinical decision-making, paving the way for more equitable and effective treatments for everyone.

With more sex-specific knowledge, better treatment regimens could be implemented for men and women, improving patient survival and quality of life.

Learn more about blood cancer:

If this article has raised any questions or concerns about your health or others, please contact your local GP.

Category: Interviews

No comments yet